“It’s so calm and solid,” says architect Beth Cameron, of Makers of Architecture. “So many people we’ve spoken to have said, ‘Oh, I didn’t know you were doing a renovation.’ Everyone who doesn’t know the project, in fact. That’s quite a lovely feeling.”

Partly, that’s because of the location. The new house sits high on the hill in Roseneath, Te Whanganui-a-Tara. Built in a former garden of an old villa, on a street of old wooden houses, it looks back over the harbour to Oriental Bay and the city. It’s a highly gentrified, genteel sort of area: villas with multiple renovations, and the odd new-build.

And it’s partly because the house is in such a high wind zone that it’s engineered to a much greater degree than we’re used to in Aotearoa, with a bagged-brick base, thick walls and windows designed for the extreme weather conditions. More than that, it carries a deliberate sense of enclosure and comfort, while maintaining a sense of lightness and ease.

When the Makers team first visited the site, they were greeted by a four-metre retaining wall. At the top, there was an overgrown – but very exposed – stepped site, with a huge old pōhutukawa, an established apple tree, and what must be among the best views in the city.

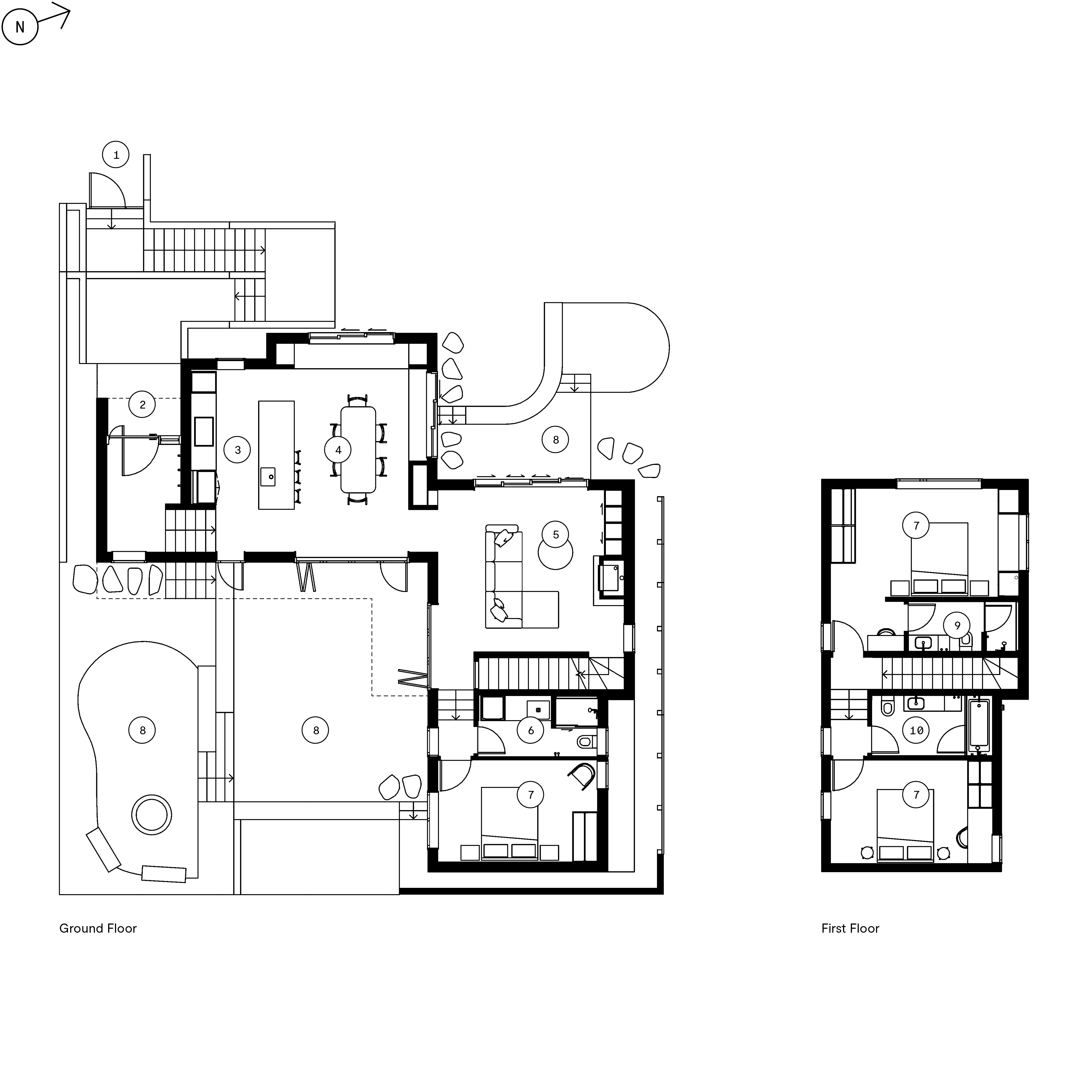

It also came with multiple overlays. It’s in the highest-possible wind zone, and there’s a height-to-boundary covenant of 4.5 metres from the natural ground level. The clients’ request for three bedrooms, two bathrooms, generous living areas and lots of outdoor space was going to take a degree of planning that can only be described as a Rubik’s cube crossed with a game of Tetris. “I come up here and I’m kind of surprised it came together as well as we hoped it would,” says Cameron. There were further challenges: the design needed to keep stormwater onsite, then release it slowly, in times of heavy rain. On this tiny site, the only place for that water to go was under the dining-room floor. There’s a concrete slab, then a heavy-duty floating timber floor. In between them are enormous water bladders, which the clients use to water their garden.

The first step was to make the site buildable. For this, Cameron and partner Jae Warrander turned to their sister business, Makers Fabrication. They established new stairs and a new 4.5-metre retaining wall, allowing access to what would become the front door. After toying with the idea of prefabricating the house and helicoptering it in, the team landed on a more traditional approach in which everything came in or out by hand. From there, they set about designing a house that steps up through five levels in two wings across the natural slope of the site, pivoting around an established pōhutukawa to create distinct outdoor areas to the north and south. “There are these existing bits of landscape which give connections back to the site,” says Warrander, “and points for us to build around – especially the pōhutukawa.”

While the prevailing wind is in the north, the house can also cop a southerly, so the team used the bulk of the building to create two courtyards. The pōhutukawa dictated how far forward the house could sit on the site. “It meant we weren’t chasing every view,” says Warrander. “That gives the house some foreground and relief – a bit of breathing room.”

Once you get to the top of the stairs, breathing lightly, you’re greeted by an oversized wooden front door which opens into a double-height entry. From here, it’s a half-level up to the kitchen-dining space and then on through to the living room. Both areas give onto the sheltered south-facing courtyard on one side and the northern courtyard on the other. At the end of this wing, the house turns away from the pōhutukawa. It’s what Warrander describes as a “hinge”, forming the second wing that steps back from the slope. Above, two bedrooms and two bathrooms are tucked up into the pitched roof. Below, there’s a guest bedroom and a combined bathroom-laundry.

“The house really dances with the site,” says Cameron. “There are these moments of expansion and contraction – spaces that open out or draw in, depending on their use and their relationship to the landscape.” The bedrooms are snug but lofty, the living area expansive, while the kitchen and entry provide moments of pause.

With its bagged-brick walls, medley of roof forms and painted pilotis holding up the rear verandah, there is a distinct sense of permanence and history at play. “There’s this real weightiness to the house,” says Warrander. “The brick in particular gives the home a lovely grounded quality, and helps articulate the building form in a beautiful way.”

Inside, the house feels warm, settled and deeply comfortable. An understated palette of rosewood and washed brick is complemented by earthy brown tones. It’s quietly expressive, tactile rather than showy. It’s also really quiet: thick brick walls and thermally modified glazing dampen sound, while a ventilation system brings in fresh air, even when the house is closed up tight. The northern windows along the face frame the view beautifully. They’re not oversized, but are carefully placed. “They wanted it to be cosy and they wanted to frame the view rather than be exposed to it,” says Cameron. “And with the wind load, we couldn’t have made them bigger even if we wanted to.”

The southern side is much less constrained, with bigger openings leading onto the sheltered courtyard that catches the afternoon sun, looking out into that apple tree they worked so hard to keep. With landscaping by James Walkinshaw, of Xanthe White Design, this peaceful space is all the more remarkable for being at the top of a very windy hill. You sit in the courtyard, looking straight through the house at the view, feeling secure, even cossetted, by its bulk. “In the evening, everything starts twinkling inside and out before it’s fully dark,” says Cameron. “It’s quite breathtaking – almost like being in a movie. ”

1. Street access

2. Entry

3. Kitchen

4. Dining

5. Living

6. Laundry/Bathroom

7. Bedroom

8. Patio

9. Ensuite

10. Bathroom