To listen to a podcast by Charlotte Ryan inspired by this house, click here. Mint-condition modernism is thin on the ground in Aotearoa. Sure, mid-century homes are revered for their form, materiality and enduring style, but as time and trends have drifted into a more open-plan way of life, many of these homes have been reshaped, renovated or erased altogether. Not this one. Designed by John Scott, this family home in Ahuriri Napier stands perfectly preserved. Commissioned by Colin and Pat Stuart in 1976, it was completed three years later, and the couple spent the rest of their lives loving and meticulously maintaining the whare. As kaitiaki, their unwavering commitment to honouring the architectural integrity of Scott’s design is admirable: the house survives not just in form, but feeling. The only updates made in its almost-50-year existence have been a new fireplace (upgraded to meet current compliance) and carpet.

The four-bedroom house sits on a tree-ringed site in a quiet corner of suburbia. It’s unassuming from the street, but anyone familiar with the materiality and form of mid-century design will recognise Scott’s hand. Concrete blockwork, small gables and disciplined geometry hint at the style and warmth within. Inside, vaulted mataī ceilings, timber panelling and cork floors provide rich contrast to the painted block walls. A modest footprint feels more generous thanks to high ceilings and thoughtful spatial planning. Fin walls subtly define spaces in the open-plan living area, where windows and glazed doors foster a connection to the environment. Standard-issue joinery has no place here; instead, each opening is unique, designed to best capture the light and land.

“The Stuart House stands as an immaculate example of John Scott’s work, a whare kāinga and a true taonga,” says his granddaughter, architect Hana Scott. “It reflects a period of radical innovation in New Zealand architecture, when ideas were developing in dialogue with environment, people, and material honesty.” Like much of Scott’s work, this home fuses influences from his upbringing, Catholic and architectural education, time spent working at Group Architects, Māori values and his peers. “He was an observer of people and place, deeply aware of how buildings affect our hauora, our sense of wellbeing and connectedness,” Hana adds.

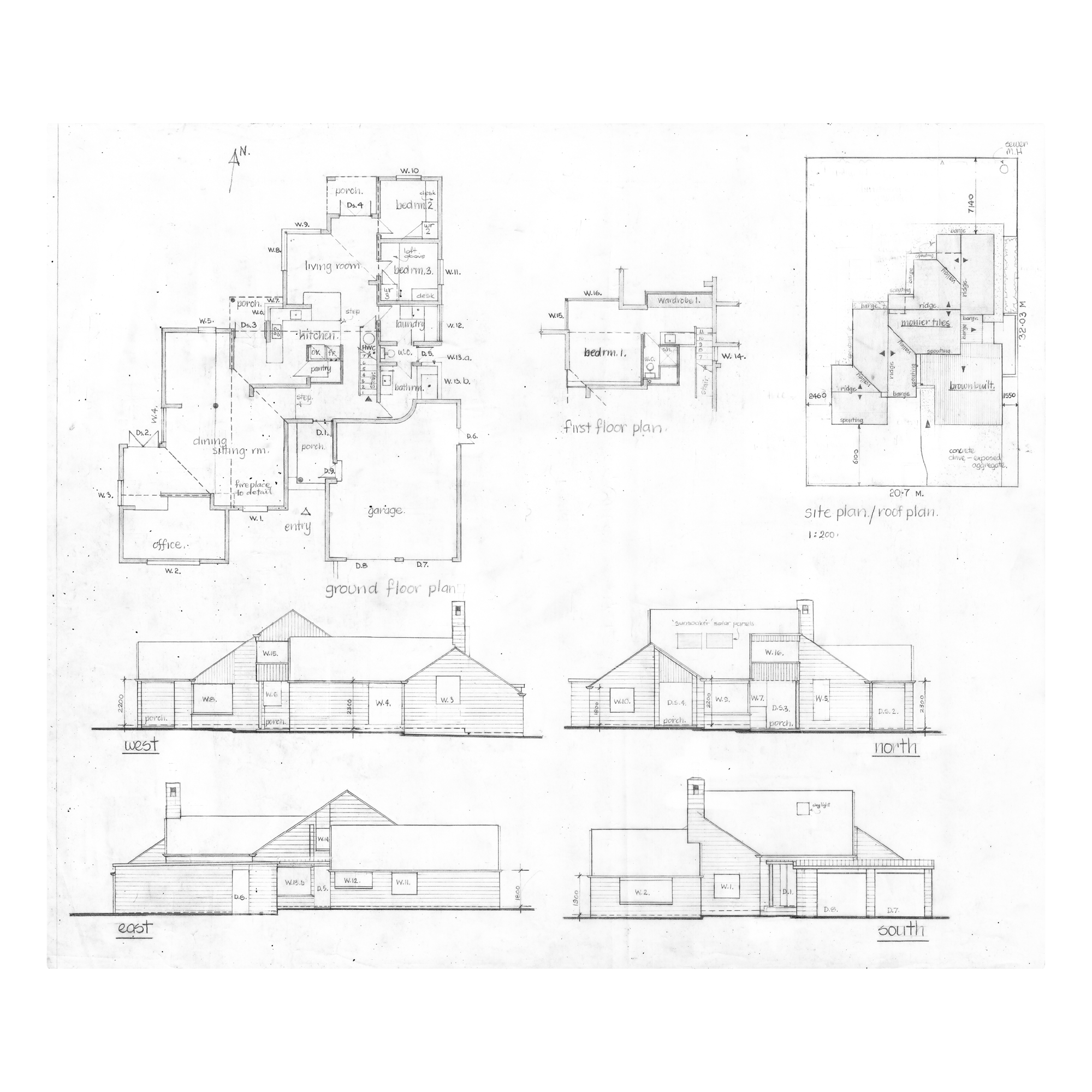

The architect’s reverence for craftsmanship resonates throughout the home. Built by Ian Kepka, it demonstrates how Scott created space for design and skill to shine, uncovering unique ways to interpret a standard feature. The internal timber doors open on a carved pivot rather than hinges; exposed roof beams are treated as part of the architecture rather than the structure; and the original sketches show plans for a Māori carving that would sit above the fridge, which, for reasons unknown, was never realised.

That L-shaped kitchen is a time capsule in timber and tile. Unchanged since construction, it’s still adorned with the original Frigidaire oven, hobs, and brown mosaic-tile bench. At one end, the counter doubles as a casual dining perch; at the other, it feeds through to the more formal dining area. Compact by contemporary standards, the angular layout works hard as a cookspace, gathering place and connecting link through the heart of the home. This clever manipulation of space and scale developed throughout Scott’s career. His designs incorporated split-levels, stepped floor plans and surprising shifts in scale, giving purpose to transitional spaces. Here, that plays out in the landing area off the primary suite upstairs. Rather than enclosing it into the bedroom, Scott left it open to overlook the living and dining area – an unexpected, almost playful gesture that turns what could’ve been a dead zone into something dynamic.

The remaining bedrooms and laundry are on the lower level. In the family bathroom there’s a particularly nice moment where the tub juts out from the home in a glazed box. While it now looks out to a tree-lined fence, there was originally no divider between this house and the neighbours, making bath time a rather risqué endeavour. The sunshine-yellow ceiling is (of course) original, complemented by pockets of cocoa brown and orange elsewhere in the whare.

The term “house proud” doesn’t begin to do justice to the Stuarts’ near half-century of guardianship. Their fastidious care and unwavering dedication to maintaining the home leave us with a rare, unedited snapshot of Scott’s domestic design in its purest form. Unsurprisingly, the house drew huge attention when it hit the market, and the new owners – Chris Evans, Justine Brown and their two teenage daughters – are intent on continuing the Stuarts’ legacy. Evans is already sourcing and stockpiling vintage fixtures and hardware for future maintenance. His mantra is simple: restore, don’t replace.

For John Scott’s whānau, the home is particularly significant. “The Stuart House is a reminder of a time when architecture in Aotearoa was deeply thoughtful, rooted in connection, crafted with integrity, and made to lift the human spirit,” says Hana Scott. When the whare changed hands earlier this year, John Scott’s daughter Ema Scott performed a blessing to mark the shift in guardianship. She composed a karakia that paid tribute to the home and her father – a beautiful way to end one chapter and begin another. Simply translated, it read, “May it be that our parents know that we honour them and their dedication in creating a legacy of design for which all of us continue to love and appreciate.”